|

1 октября отправила на проверку первое задание, до сих пор не проверено, по этой причине не могу пройти последующие тесты. |

Overview of ESOL issues

Now consider the following extract:

Age

The age of our students is a major factor in our decisions about how and what to teach. People of different ages have different needs, competences and cognitive skills; we might expect children of primary age to acquire much of a foreign language through play, for example, whereas for adults we can reasonably expect a greater use of abstract thought.

One of the most common beliefs about age and language learning is that young children learn faster and more effectively than any other age group. Most people can think of examples which appear to bear this out - as when children move to a new country and appear to pick up a new language with remarkable ease. However, as we shall see, this is not always true of children in that situation, and the story of child language facility may be something of a myth.

It is certainly true that children who learn a new language early have a facility with the pronunciation which is sometimes denied older learners. Lynne Cameron suggests that children 'reproduce the accent of their teachers with deadly accuracy' (2003: 111). Carol Read recounts how she hears a young student of hers saying Listen. Quiet now. Attention, please! in such a perfect imitation of the teacher that 'the thought of parody passes through my head' (2003: 7).

Apart from pronunciation ability, however, it appears that older children (that is children from about the age of 12) 'seem to be far better learners than younger ones in most aspects of acquisition, pronunciation excluded' (Yu, 2006: 53). Patsy Lightbown and Nina Spada, reviewing the literature on the subject, point to the various studies showing that older children and adolescents make more progress than younger learners (2006: 67-74).

The relative superiority of older children as language learners (especially in formal educational settings) may have something to do with their increased cognitive abilities, which allow them to benefit from more abstract approaches to language teaching. It may also have something to do with the way younger children are taught. Lynne Cameron, quoted above, suggests that teachers of young learners need to be especially alert and adaptive in their response to tasks and have to be able to adjust activities on the spot.

It is not being suggested that young children cannot acquire second languages successfully.

As we have already said, many of them achieve significant competence, especially in bilingual situations. But in learning situations, teenagers are often more effective learners. Yet English is increasingly being taught at younger and younger ages. This may have great benefits in terms of citizenship, democracy, tolerance and multiculturalism but especially when there is ineffective transfer of skills and methodology from primary to secondary school, early learning does not always appear to offer the substantial success often claimed for it.

Nor is it true that older learners are necessarily ineffective language learners. Research has shown that they 'can reach high levels of proficiency in their second language' (Lightbown and Spada 2006: 73). They may have greater difficulty in approximating native speaker pronunciation than children do, but sometimes this is a deliberate (or even subconscious) retention of their cultural and linguistic identity.

In what follows we will consider students at different ages as if all the members of each age group are the same. Yet each student is an individual with different experiences both in and outside the classroom. Comments here about young children, teenagers and adults can only be generalisations. Much also depends upon individual learner differences and upon motivation (see below).

Young children

Young children, especially those up to the ages of nine or ten, learn differently from older children, adolescents and adults in the following ways:

- They respond to meaning even if they do not understand individual words.

- They often learn indirectly rather than directly - that is they take in information from all sides, learning from everything around them rather than only focusing on the precise topic they are being taught.

- Their understanding comes not just from explanation, but also from what they see and hear and, crucially, have a chance to touch and interact with.

- They find abstract concepts such as grammar rules difficult to grasp.

- They generally display an enthusiasm for learning and a curiosity about the world around them.

- They have a need for individual attention and approval from the teacher.

- They are keen to talk about themselves and respond well to learning that uses themselves and their own lives as main topics in the classroom.

- They have a limited attention span; unless activities are extremely engaging, they can get easily bored, losing interest after ten minutes or so.

lt is important, when discussing young learners, to take account of changes which take place within this varied and varying age span. Gul Keskil and Pasa Tevfik Cephe, for example, note that 'while pupils who are 10 and 11 years old like games, puzzles and songs most, those who are 12 and 13 years old like activities built around dialogues, question-and-answer activities and matching exercises most' (2001: 61).

Various theorists have described the way that children develop and the various ages and stages they go through. Piaget suggested that children start at the sensori-motor stage, and then proceed through the intuitive stage and the concrete-operational stage before finally reaching the formal operational stage where abstraction becomes increasingly possible. Leo Vygotsky emphasised the place of social interaction in development and the role of a 'knower' providing 'scaffolding' to help a child who has entered the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) where they are ready to learn new things. Both Erik Erikson and Abraham Maslow saw development as being closely bound up in the child's confidence and self-esteem, while Reuven Feuerstein suggested that children's cognitive structures are infinitely modifiable with the help of a modifier - much like Vygotsky's knower.

But however we describe the way children develop (and though there are significant differences between, say, a four year old and a nine year old), we can make some recommendations about younger learners in general, that is children up to about ten and eleven.

In the first place, good teachers at this level need to provide a rich diet of learning experiences which encourage their students to get information from a variety of sources. They need to work with their students individually and in groups, developing good and affective relationships. They need to plan a range of activities for a given time period, and be flexible enough to move on to the next exercise when they see their students getting bored.

Teachers of young learners need to spend time understanding how their students think and operate. They need to be able to pick up on their students' current interests so that they can use them to motivate the children. And they need good oral skills in English since speaking and listening are the skills which will be used most of all at this age. The teacher's pronunciation really matters here, too, precisely because, as we have said, children imitate it so well.

All of this reminds us that once a decision has been taken to teach English to younger learners, there is a need for highly skilled and dedicated teaching. This may well be the most difficult (but rewarding) age to teach, but when teachers do it well (and the conditions are right), there is no reason why students should not defy some of the research results we mentioned above and be highly successful learners - provided, of course, that this success is followed up as they move to a new school or grade.

We can also draw some conclusions about what a classroom for young children should look like and what might be going on in it. First of all, we will want the classroom to be bright and colourful, with windows the children can see out of, and with enough room for different activities to be taking place. We might expect the students to be working in groups in different parts of the classroom, changing their activity every ten minutes or so. 'We are obviously,' Susan Halliwell writes, 'not talking about classrooms where children spend all their time sitting still in rows or talking only to the teacher' (1992: 18). Because children love discovering things, and because they respond well to being asked to use their imagination, they may well be involved in puzzle-like activities, in making things, in drawing things, in games, in physical movement or in songs. A good primary classroom mixes play and learning in an atmosphere of cheerful and supportive harmony.

Adolescents

It is strange that, despite their relative success as language learners, adolescents are often seen as problem students. Yet with their greater ability for abstract thought and their passionate commitment to what they are doing once they are engaged, adolescents may well be the most exciting students of all. Most of them understand the need for learning and, with the right goals, can be responsible enough to do what is asked of them.

It is perfectly true that there are times when things don't seem to go very well. Adolescence is bound up, after all, with a pronounced search for identity and a need for self-esteem; adolescents need to feel good about themselves and valued. All of this is reflected in the secondary student who convincingly argued that a good teacher 'is someone who knows our names' (Harmer 2007: 26). But it's not just teachers, of course; teenage students often have an acute need for peer approval, too (or, at the very least, are extremely vulnerable to the negative judgements of their own age group).

We should not become too preoccupied with the issue of disruptive behaviour, for while we will all remember unsatisfactory classes, we will also look back with pleasure on those groups and lessons which were successful. There is almost nothing more exciting than a class of involved young people at this age pursuing a learning goal with enthusiasm. Our job, therefore, must be to provoke student engagement with material which is relevant and involving. At the same time, we need to do what we can to bolster our students' self-esteem, and be conscious, always, of their need for identity.

Herbert Puchta and Michael Schratz see problems with teenagers as resulting, in part, from ' ... the teacher's failure to build bridges between what they want and have to teach and their students' worlds of thought and experience' (1993: 4). They advocate linking language teaching far more closely to the students' everyday interests through, in particular, the use of 'humanistic' teaching. Thus, material has to be designed at the students' level, with topics which they can react to. They must be encouraged to respond to texts and situations with their own thoughts and experiences, rather than just by answering questions and doing abstract learning activities. We must give them tasks which they are able to do, rather than risk humiliating them.

We have come some way from the teaching of young children. We can ask teenagers to address learning issues directly in a way that younger learners might not appreciate. We are able to discuss abstract issues with them. Indeed, part of our job is to provoke intellectual activity by helping them to be aware of contrasting ideas and concepts which they can resolve for themselves - though still with our guidance. There are many ways of studying language and practising language skills, and most of these are appropriate for teenagers.

Adult learners

Adult language learners are notable for a number of special characteristics:

- They can engage with abstract thought. This suggests that we do not have to rely exclusively on activities such as games and songs - though these may be appropriate for some students.

- They have a whole range of life experiences to draw on.

- They have expectations about the learning process, and they already have their own set patterns of learning.

- Adults tend, on the whole, to be more disciplined than other age groups, and, crucially, they are often prepared to struggle on despite boredom.

- They come into classrooms with a rich range of experiences which allow teachers to use a wide range of activities with them.

- Unlike young children and teenagers, they often have a clear understanding of why they are learning and what they want to get out of it. Many adults are able to sustain a level of motivation by holding on to a distant goal in a way that teenagers find more difficult.

However, adults are never entirely problem-free learners, and they have a number of characteristics which can sometimes make learning and teaching problematic.

- They can be critical of teaching methods. Their previous learning experiences may have predisposed them to one particular methodological style which makes them uncomfortable with unfamiliar teaching patterns. Conversely, they may be hostile to certain teaching and learning activities which replicate the teaching they received earlier in their educational careers.

- They may have experienced failure or criticism at school which makes them anxious and under-confident about learning a language.

- Many older adults worry that their intellectual powers may be diminishing with age. They are concerned to keep their creative powers alive, to maintain a 'sense of generativity' (Williams and Burden 1997: 32). However, as Alan Rogers points out, this generativity is directly related to how much learning has been going on in adult life before they come to a new learning experience (1996: 54).

Good teachers of adults take all of these factors into account. They are aware that their students will often be prepared to stick with an activity for longer than younger learners (though too much boredom can obviously have a disastrous effect on motivation). As well as involving their students in more indirect learning through reading, listening and communicative speaking and writing, they also allow them to use their intellects to learn consciously where this is appropriate. They encourage their students to use their own life experience in the learning process, too.

As teachers of adults we should recognise the need to minimise the bad effects of past learning experiences. We can diminish the fear of failure by offering activities which are achievable and by paying special attention to the level of challenge presented by exercises. We need to listen to students' concerns, too, and, in many cases, modify what we do to suit their learning tastes.

Learner differences

The moment we realise that a class is composed of individuals (rather than being some kind of unified whole), we have to start thinking about how to respond to these students individually so that while we may frequently teach the group as a whole, we will also, in different ways, pay attention to the different identities we are faced with.

Aptitude and intelligence

Some students are better at learning languages than others. At least that is the generally held view, and in the 1950s and 1960s it crystallised around the belief that it was possible to predict a student's future progress on the basis of linguistic aptitude tests. But it soon became clear that such tests were flawed in a number of ways. They didn't appear to measure anything other than general intellectual ability even though they ostensibly looked for linguistic talents. Furthermore, they favoured analytic-type learners over their more 'holistic' counterparts, so the tests were especially suited to people who have little trouble doing grammar-focused tasks. Those with a more 'general' view of things - whose analytical abilities are not so highly developed, and who receive and use language in a more message-oriented way - appeared to be at a disadvantage. In fact, analytic aptitude is probably not the critical factor in success. Peter Skehan, for example, believes that what distinguishes exceptional students from the rest is that they have unusual memories, particularly for the retention of things that they hear (1998: 234).

Another damning criticism of traditional aptitude tests is that while they may discriminate between the most and the least 'intelligent' students, they are less effective at distinguishing between the majority of students who fall between these two extremes. What they do accomplish is to influence the way in which both teachers and students behave. It has been suggested that students who score badly on aptitude tests will become demotivated and that this will then contribute to precisely the failure that the test predicted. Moreover, teachers who know that particular students have achieved high scores will be tempted to treat those students differently from students whose score was low. Aptitude tests end up being self-¬fulfilling prophecies whereas it would be much better for both teacher and students to be optimistic about all of the people in the class.

It is possible that people have different aptitudes for different kinds of study. However, if we consider aptitude and intelligence for learning language in general, our own experience of people we know who speak two or more languages can only support the view that ‘learners with a wide variety of intellectual abilities can be successful language learners. This is especially true if the emphasis is on oral communication skills rather than metalinguistic knowledge' (Lightbown and Spada 2006: 185).

Good learner characteristics

Another line of enquiry has been to try to tease out what a 'good learner' is. If we can narrow down a number of characteristics that all good learners share, then we can, perhaps, cultivate these characteristics in all our students.

Neil Naiman and his colleagues included a tolerance of ambiguity as a feature of good learning, together with factors such as positive task orientation (being prepared to approach tasks in a positive fashion), ego involvement (where success is important for a student's self-image), high aspirations, goal orientation and perseverance (Naiman et al 1978).

Joan Rubin and Irene Thompson listed no fewer than 14 good learner characteristics, among which learning to live with uncertainty (much like the tolerance of ambiguity mentioned above) is a notable factor (Rubin and Thompson 1982). But the Rubin and Thompson version of a good learner also mentions students who can find their own way (without always having to be guided by the teacher through learning tasks), who are creative, who make intelligent guesses, who make their own opportunities for practice, who make errors work for them not against them, and who use contextual clues.

Much of what various people have said about good learners is based on cultural assumptions which underpin much current teaching practice in western-influenced methodologies.

Different cultures value different learning behaviours, however. Our insistence upon one kind of 'good learner' profile may encourage us to demand that students should act in class in certain ways, whatever their learning background. When we espouse some of the techniques mentioned above, we risk imposing a methodology on our students that is inimical to their culture. Yet it is precisely because this is not perhaps in the best interests of the students. Furthermore, some students may not enjoy grammar exercises, but this does not mean they are doomed to learning failure. There is nothing wrong with trying to describe good language learning behaviour. Nevertheless, we need to recognise that some of our assumptions are heavily culture¬-bound and that students can be successful even if they do not follow these characteristics to the letter.

Learner styles and strategies

A preoccupation with learner personalities and styles has been a major factor in psycholinguistic research. Are there different kinds of learner? Are there different kinds of behaviour in a group? How can we tailor our teaching to match the personalities in front of us?

Keith Willing, working with adult students in Australia, has suggested four learner categories:

Convergers: these are students who are by nature solitary, prefer to avoid groups, and who are independent and confident in their own abilities. Most importantly they are analytic and can impose their own structures on learning. They tend to be cool and pragmatic.

Conformists: these are students who prefer to emphasise learning 'about language' over learning to use it. They tend to be dependent on those in authority and are perfectly happy to work in non-communicative classrooms, doing what they are told. A classroom of conformists is one which prefers to see well-organised teachers.

Concrete learners: though they are like conformists, they also enjoy the social aspects of learning and like to learn from direct experience. They are interested in language use and language as communication rather than language as a system. They enjoy games and groupwork in class.

Communicative learners: these are language use oriented. They are comfortable out of class and show a degree of confidence and a willingness to take risks which their colleagues may lack. They are much more interested in social interaction with other speakers of the language than they are with analysis of how the language works. They are perfectly happy to operate without the guidance of a teacher.

We should do as much as we can to understand the individual differences within a group. We should try to find descriptions that chime with our own perceptions, and we should endeavour to teach individuals as well as groups.

Individual variations

If some people are better at some things than others - better at analysing, for example - this would indicate that there are differences in the ways individual brains work. It also suggests that people respond differently to the same stimuli. How might such variation determine the ways in which individual students learn most readily? How might it affect the ways in which we teach? There are two models in particular which have tried to account for such perceived individual variation, and which teachers have attempted to use for the benefit of their learners.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming: according to practitioners of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), we use a number of 'primary representational systems' to experience the world. These systems are described in the acronym 'VAKOG' which stands for Visual (we look and see), Auditory (we hear and listen), Kinaesthetic (we feel externally, internally or through movement), Olfactory (we smell things) and Gustatory (we taste things).

Most people, while using all these systems to experience the world, nevertheless have one 'preferred primary system' (Revell and Norman 1997: 31). Some people are particularly stimulated by music when their preferred primary system is auditory, whereas others, whose primary preferred system is visual, respond most powerfully to images. An extension of this is when a visual person 'sees' music, or has a strong sense of different colours for different sounds. The VAKOG formulation, while somewhat problematic in the distinctions it attempts to make, offers a framework to analyse different student responses to stimuli and environments.

NLP gives teachers the chance to offer students activities which suit their primary preferred systems.

MI theory: MI stands for Multiple Intelligences, a concept introduced by the Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner. In his book Frames of Mind, he suggested that we do not possess a single intelligence, but a range of intelligences (Gardner 1983). He listed seven of these: Musical/rhythmical, Verbal/linguistic, Visual/spatial, Bodily/kinaesthetic, Logical/mathematical, Intrapersonal and Interpersonal. All people have all of these intelligences, he said, but in each person one (or more) of them is more pronounced. This allowed him to predict that a typical occupation (or 'end state') for people with a strength in logical/mathematical intelligence is that of the scientist, whereas a typical end state for people with strengths in visual/spatial intelligence might well be that of the navigator. The athlete might be the typical end state for people who are strong in bodily/kinaesthetic intelligence, and so on. Gardner has since added an eighth intelligence which he calls Naturalistic intelligence (Gardner 1993) to account for the ability to recognise and classify patterns in nature; Daniel Goleman has added a ninth 'emotional intelligence' (Goleman 1995). This includes the ability to empathise, control impulse and self-motivate.

If we accept that different intelligences predominate in different people, it suggests that the same learning task may not be appropriate for all of our students. While people with a strong logical/mathematical intelligence might respond well to a complex grammar explanation, a different student might need the comfort of diagrams and physical demonstration because their strength is in the visual/spatial area. Other students who have a strong interpersonal intelligence may require a more interactive climate if their learning is to be effective.

information

What to do about individual differences

Faced with the different descriptions of learner types and styles which have been listed here, it may seem that the teacher's task is overwhelmingly complex. We want to satisfy the many different students in front of us, teaching to their individual strengths with activities designed to produce the best results for each of them, yet we also want to address our teaching to the group as a whole.

Our task as teachers will be greatly helped if we can establish who the different students in our classes are and recognise how they are different. We can do this through observation or through more formal devices. For example, we might ask students what their learning preferences are in questionnaires with items (perhaps in the students' first language) such as the following:

However, we might not want to view some of the results of NLP and MI tests uncritically. This is partly because neither MI theory nor NLP have been subjected to any kind of rigorous scientific evaluation. However, it is clear that they both address self-evident truths - namely that different students react differently to different stimuli and that different students have different kinds of mental abilities. And so, as a result of getting information about individuals, we will be in a position to try to organise activities which provide maximal advantage to the many different people in the class, offering activities which favour, at different times, students with different learning styles. It is then up to us to keep a record of what works and what doesn't, either formally or informally. We can also ask our students (either face to face, or, more effectively, through written feedback) how they respond to these activities. Such feedback, coupled with questionnaires and our own observation, helps us to build a picture of the best kinds of activity for the mix of individuals in a particular class. This kind of feedback enables us, over time, to respond to our students with an appropriate blend of tasks and exercises.

This does not mean, of course, that everyone will be happy all of the time (as the feedback above shows). On the contrary, it clearly suggests that some lessons (or parts of lessons ) will be more useful for some students than for others. But if we are aware of this and act accordingly, then there is a good chance that most of the class will be engaged with the learning process most of the time.

There is one last issue which should be addressed. We have already referred to the danger of pre-judging student ability through aptitude tests, but we might go further and worry about fixed descriptions of student differences. If students are always the same (in terms of their preferred primary system or their different intelligences), this suggests that they cannot change. Yet all learning is, in a sense, about change of one kind or another and part of our role as teachers is to help students effect change. Our job is surely to broaden students' abilities and perceptions, not merely to reinforce their natural prejudices or emphasise their limitations.

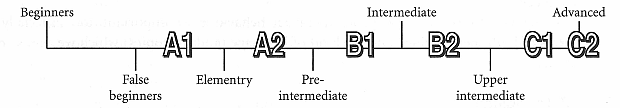

Language Levels

In recent years, the Council of Europe and the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) have been working to define language competency levels for learners of a number of different languages. The result of these efforts is the Common European Framework (a document setting out in detail what students 'can do' at various levels) and a series of ALTE levels ranging from A1 (roughly equivalent to elementary level) to C2 (very advanced). Figure 5.2 shows the different levels in sequence.

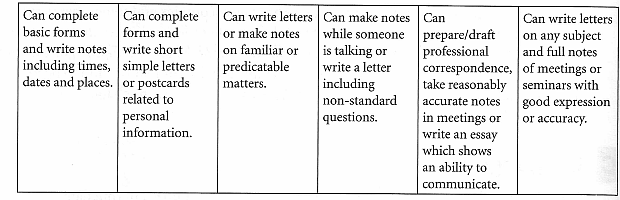

ALTE has produced 'can do' statements to try to show students, as well as teachers, what these levels mean, as the example in Figure 5.3 for the skill of writing demonstrates (A1 is at the left, C2 at the right).

ALTE levels and 'can do' statement are being used increasingly by coursebook writers and curriculum designers, not only in Europe but across much of the language-learning world. They are especially useful when translated into the students' L1 because they allow students to say what they can do, rather than having to be told by the teacher what standard they measure up against.