|

1 октября отправила на проверку первое задание, до сих пор не проверено, по этой причине не могу пройти последующие тесты. |

Parts and stages of a lesson

Now consider the following extract:

What teachers do next

In her course for language teachers, Penny Ur discussed the difference between teachers 'with 20 years' experience and those with one year's experience repeated 20 times' (Ur 1996: 317). Naturally we admire the first teacher and disapprove of (or sympathise with) the second. Nothing could be more deadening for a teacher than 20 years of repetition, especially in the interactive and dynamic world of the classroom. Our students, too, deserve teachers who are alive to the possibility of change and who keep up-to-date with what is going on, not only in the world of English language teaching, but also in the world at large.

The truth, however, is that no matter how much we enjoy meeting new students at the beginning of a new course, it is sometimes difficult to maintain a sense of excitement and engagement when using the same old lesson routines or reading texts time after time. The increasing predictability of student reactions and behaviour can - if we do not take steps to prevent it - dent even the most ardent initial enthusiasm. Teaching should be different from this, though. It can and should be a permanent process of change and growth.

At the beginning of our careers we go on teacher training courses where we are taught what to do. It is as our careers develop, however, that instead of being trained (or in addition to be trained), we should seek to develop ourselves and our teaching.

Teacher development means many different things to different people. Brian Tomlinson suggests that in a teacher development approach teachers are given new experiences to reflect and learn from (Tomlinson 2003). For him, the best of these tools is to involve teachers in writing teaching materials since when they do this they have to think carefully about what they want to do, why they want to do it and how to make it happen. Bill Templer, on the other hand, thinks that 'we need to hold up mirrors to our own practice, making more conscious what is beneath the surface' (Templer 2004). Paul Davis says that 'as development becomes more powerful, the role of the trainer will become less important' (Davis 1999). Sandra Piai was extremely impressed to hear a participant in a teacher development workshop say 'You can train me, and you can educate me, but you can't develop me - I develop' (Piai 2005: 21).

Reflection paths

Holding up mirrors to our practice (in Templer's words - see above) means being a reflective teacher. In other words, we need to think about (to reflect on) what we are doing and why. Some reflection is simply a matter of thinking about what is happening in our lessons (and our lives) as we take the metro home from work, but there are a number of more organised ways of doing this.

Keeping journals

One way of provoking self-analysis and reflection on our teaching is by keeping our own journals in which we record our thoughts about our teaching and our students. Journals are powerful reflective devices which allow us to use introspection to make sense of what is going on around us.

Journal-writing is powerful for two main reasons. In the first place, the act of writing the journal forces us to try to put into words thoughts which, up till then, are inchoate, offering, in this condition, little chance for real introspection. Secondly, the act of reading our own journals makes us engage again with what we experienced, felt or worried about. As a result of this re-engagement, we might quite possibly come to conclusions about what to do next.

Negative and positive

If real development can only come from within, then it is by looking inside ourselves and seeking to understand or change what we find there that is likely to be the most effective way of moving forward and making things better.

Linda Bawcom, in an article devoted to preventing stress and countering teacher burnout, suggests making lists and seeing what they tell us. For example, we might draw up a list of professional priorities, such as the one in Figure 1. In the left-hand column we say what actually happens by numbering the items 1-12. Then, in the right-hand column, we re-prioritise the items as we would like them to be. The difference between the reality and what we wish for gives us the beginnings of a development plan.

Recording ourselves

Another way of reflecting upon our own teaching practice is to record ourselves. Bill Templer (see above) suggests using a cheap tape recorder which we can leave running during the lesson. When the lesson is over, we can listen to the tape to remind us of what went on. Frequently, this will lead us to reflect on what happened and perhaps cause us to think of how we might do things differently in the future.

Many teachers have derived benefit (and some surprise) from having their lessons filmed.

Watching ourselves at work is often slightly uncomfortable, but it can also show us things which we were not aware of.

Professional literature

There is much to be learnt from the various methodology books, journals and magazines produced for teachers of English. Books and articles written by teachers and theorists will often open our eyes to new possibilities. They may also form part of action research or 'search' and 'research' cycles (see below), either by raising an issue which we want to focus on or by helping us to formulate the kinds of questions we wish to ask.

There are a number of different journals which cater for different tastes; whereas some report on academic research, others prefer to describe classroom activities in detail, often with personal comment from the writer. Some journals impose a formal style on their contributors, whereas others allow for a variety of approaches, including letters and short reports. Some journals are now published exclusively on the Internet, while others have Internet archives of past articles.

When teachers join professional teacher organisations, they often receive that organisation's journal or newsletter. Members of special interest groups (such as the Teacher Development Special Interest Group - TD SIG – of IATEFL) will also get publications for that SIG. These newsletters and journals are a valuable way of keeping in touch with what is going on in the world of English language teaching. Not only do they inform us about new developments and ideas, but they also keep us in touch with colleagues whose concerns, it soon becomes apparent, are similar to ours.

Action research

This starts when we identify an issue we wish to investigate. We may want to know more about our learners and what they find motivating and challenging. We might want to learn more about ourselves as teachers - how effective we are, how we look at our students, how we would look at ourselves if we were observing our own teaching. We might want to gauge the interest generated by certain topics or judge the effectiveness of certain activity types. We might want to see if an activity would work better done in groups rather than pairs, or investigate whether reading is more effective with or without pre-teaching vocabulary. We might want to find out why something isn't working.

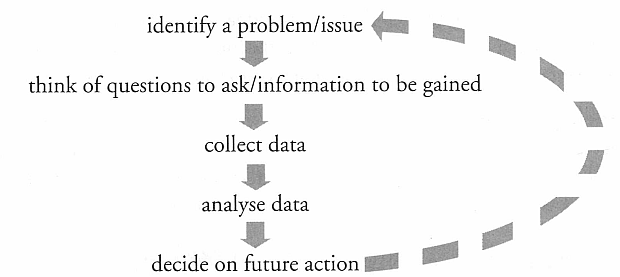

Whichever of these issues we choose, we will want to formulate questions we want answered so that we can decide how we are going to gather data. Having collected the data, we analyse the results, and it is on the basis of these results that we decide what to do next. We may then subject this new decision to the same examination that the original issue generated (this possibility is reflected by the broken line in Figure 1). Alternatively, having resolved one issue, we may focus on a different problem and start the process afresh for that issue.

Gathering data

In order for our inquiry or case study to be effective, we have to gather data. There are many ways of doing this, but two of them have already been mentioned above. For example, we might decide to keep a journal about one specific aspect of teaching (e.g. what happens when students work in groups) and write entries about this at the end of every day's teaching. After, say, 14 days of this, we will have a lot of evidence. Alternatively, we might record ourselves (or have ourselves filmed) doing particular tasks so that we can assess their effectiveness. But there are other data-gathering methods, too.

- Observation tasks: we can design data-gathering worksheets which are easy to use, but which will give us valuable information. For example, we could have a list of student names in a column. Each time a student says something, we can put a tick against his or her name. After a few lessons we will have a much clearer and more accurate idea of individual participation.

- >Interviews: we can interview students and colleagues about activities, materials, techniques and procedures.

- >Written questionnaires: questionnaires, which are sometimes more effective than the interviews we described above, can get respondents to answer open questions such as How did you feel about activity X?, yes/no questions such as Did you find activity X easy? or questions which ask for some kind of rating response.

- >Breaking rules and changing environments: in a groundbreaking work, John Fanselow (1987) suggested that one way of developing is to break our own rules and see what happens. If we normally teach one way, in other words, we should try teaching in the opposite way and see what effect it has. If we normally move around the class all the time, perhaps we should see what happens if we spend the whole lesson sitting in the same place. The results may be surprising and will never be less than interesting.

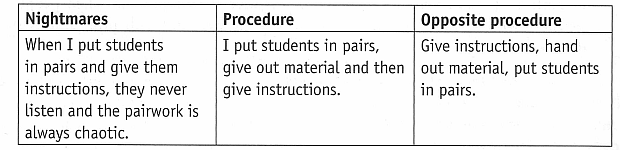

One way to help us think about doing things differently is a technique called 'Cataloguing nightmares' (see Figure 3). In this we complete the left - hand column with a list of the things that go wrong - or that we are frightened might go wrong - in our lessons. In the next column, we say what happens which makes these things go wrong. Finally, in the right-hand column, we write down an opposite procedure from the one described in the middle column. We now have a plan of action for breaking rules - or at least completely upending the routines we use. Our new 'opposite procedure' may not work, but at least it will allow us to view the problem differently and maybe gain some insights into how to change things (again) in the future.

Developing with others

Not all reflection, reading or action research needs to be done by teachers working alone. There are many ways teachers can confer with each other and develop together, either face to face or, increasingly, online.

Cooperative/collaborative development

Teachers, like anyone else, need chances to discuss what they are doing and what happens to them in class so that they can examine their beliefs and feelings. However much we have reflected on our own experiences and practice, most of us find discussing our situation with others helps us to sort things out in our own mind. Julian Edge coined the term cooperative development (Edge 1992a and b) to describe a specific kind of relationship between speakers and the people listening to them. In cooperative development 'a relationship of trust is necessary' (Edge 2003: 58) between speakers who interact with understanders; a teacher, in this case, talks to an empathetic colleague. The empathetic colleague (the understander) makes every effort to understand the speaker but crucially, in Edge's realisation, does not interpret, explain or judge what he or she is hearing. All that is necessary is for the understander to say 'This is what I'm hearing. This is what I've understood. Have I got it right?' (Edge 1992a: 65). The understander's side of the bargain is that 'she will put aside her own thoughts, ideas and evaluations in order to concentrate on understanding what the speaker has to say' (Edge 2003: 58).

This style of empathising is similar to 'co-counselling', where two people agree to meet and divide the allotted time in half so that each is a speaker and listener for an equal time period (Head and Taylor 1997: 143-144).

Peer teaching, peer observation

In our teaching lives we are frequently observed by others. It starts on teacher training courses and goes on when academic coordinators or directors of study come into our lessons as part of some quality control exercise. In all these situations the observed teacher is at a disadvantage since the observers - however sympathetically they carry out their function - have power over the teacher's future career. There are very few teachers who welcome this kind of visitation.

However, many of us would welcome the opportunity to talk to someone about a lesson we have just taught, hoping that they would help us to understand what happened at certain moments or suggest ways of making things more effective. This was the case with a teacher called Poh in Hong Kong who invited her colleague Thomas Farrell into her lessons as part of her own self-development. She wanted an outsider's view of her teaching practices, a view which was not totally dependent on her own or her students' reactions. Thomas Farrell thus became her 'critical friend' and soon noted, with interest, that even before Poh had seen his observation notes, she 'addressed most of the issues I had raised'. Perhaps Farrell had taken on a 'proactive role of promoting reflection within our friendship by acting as a catalyst for Poh to look at her teaching' (Farrell 2001: 372).

It sounds like the ideal arrangement - equal colleagues observing each other so that they (or at least one of them) can develop.

Teachers' groups

One of the most supportive environments for teachers, where real teacher development can take place, is in small teacher groups. In this situation colleagues, usually working in the same school, meet together to discuss any issues and problems which may arise in the course of their teaching.

Some teacher development meetings of this kind are organised by principals and directors of study. Outside speakers and animators are occasionally brought in to facilitate discussions. The director of studies may select a topic - in conjunction with the teachers - and then asks a member of staff to lead a session. What emerges is something halfway between bottom¬-up teacher development and top-down in-service teacher training (INSETT). At their best, such regular meetings are extremely stimulating and insightful. In many schools an INSETT coordinator is appointed to arrange a teacher development programme. Where this is done effectively, he or she will consult widely with colleagues to see what they would most like to work on and with.

Teachers' associations

There are many teachers' associations around the world. Some of them are international, such as IATEFL, based in Britain and TESOL, based in the USA; some are country-based, such as JALT (in Japan), FAAPI (in Argentina), ELICOS (in Australia) or ATECR (in the Czech Republic); still others are smaller and regional, such as APIGA (in Galicia, Spain) or CELTA (in Cambridge, England).

Teachers' associations provide two possible development opportunities:

-

Conferences and seminars: conferences, meetings and workshops allow us to hear about the latest developments in the field, take part in investigative workshops and enter into debates about current issues in theory and practice. We can 'network' with other members of the ELT community and, best of all, we learn that other people from different places, different countries and systems even, share similar problems and are themselves searching for solutions.

Perhaps the best moments in conferences are the conversations that participants have with each other after they've been to talks and workshops. As we walk out of other people's sessions, we compare notes with fellow attenders, and as we do so, we find ourselves having to justify why we have reacted as we have to what we have heard. These exchanges are often significantly more important than the sessions themselves since they offer very real (even if short) self-development opportunities as we grapple with our feelings and thoughts about what we have experienced.

- Presenting: submitting a paper or a workshop for a teachers' association meeting, whether regional, national or international, is one of the most powerful catalysts for reflecting upon our practice. When we try to work out exactly what we want to say and the best way of doing it, we are forcing ourselves to assess what we do. The challenge of a future audience sharpens our perceptions.

The virtual community

There is no real substitute for people meeting together in the same physical space to share experiences, ideas, hopes and fears. But there are alternatives, and the plethora of different sites and user groups on the Internet offers teachers considerable scope in talking to colleagues all over the world at all hours of the day or night. There are many different groups of this kind. There are also people who meet when taking part in real-time chat forums (quite apart from conference calls using audio or videoware). In the future it will be increasingly common and unsensational for people to contact each other online like this.

We have said that real face-to-face communication is always better than online discussion whether or not it takes place in real time or whether it is the result of emails posted on a group noticeboard at different times. Yet the huge advantage of online communication is the fact that someone from Ankara, say, can talk to someone from Vermont very easily - and that all the other members of the group, whether or not they are participating or lurking (i.e. reading all the postings without replying), can be members of the group wherever they are located.

Moving outwards and sideways

In order to enhance professional and personal growth, teachers sometimes need to step outside the world of the classroom where the concentration, all too frequently, is on knowledge and skill alone. There are other issues and practices which can be of immense help in making their professional understanding more profound and their working reality more rewarding.

Learning by learning

One of the best ways of reflecting upon our teaching practice is to become learners ourselves again, so that our view of the learning-teaching process is not always influenced from one side of that relationship. By voluntarily submitting ourselves to a new learning experience, especially (but not only) if this involves us in learning a new language, our view of our students' experience can be changed. As Luke Prodromou found when he decided to learn Spanish, ‘Going back to school, and being on the receiving end of the foreign language learning process, confronted me with challenge after challenge to my assumptions about good language teaching' (2002b: 58).

Supplementing teaching

One way of countering the potential sameness of a teacher's life is to increase our range of occupations and interests so that teaching becomes the fixed centre in a more varied and interesting professional life.

There are many tasks that make a valuable contribution to the teaching and learning of English. First among these is writing materials - whether these are one-off activities, longer units or whole books. Materials writing can be challenging and stimulating, and when done in tandem with teaching can provide us with powerful insights, so that both the writing and the teaching become significantly more involving and enjoyable.

Teachers can become involved in far more than just materials (or article) writing, however.

The various exam boards such as Cambridge ESOL, Trinity Exams, TOEFL, TOEIC and others are always on the lookout for markers, examiners and item writers. As with publishing, teachers who are interested in this area should find out the name of the relevant subject officer and write to them, expressing their interest and saying who they are and where they work.

Many people now set up their own websites where they provide material either by subscription or free of charge. It is no longer difficult or expensive to record material which can be made available as MP3 files (and so be downloaded as podcasts). Other teachers help to organise entertainments for their students or run drama groups, sports teams or conversation get-togethers.

Many teachers see a change of teaching sector as a developmental move, both as a way of researching teaching and also as a way of making life more challenging and more interesting. Perhaps the most interesting move, in this sense, is to become involved in training teachers since this is not only extremely rewarding but also forces us to examine what we do and how we do it in a way that has huge developmental benefits. But any move to a different kind of teaching (such as one-to-one, exam teaching or business English, if these are things we have not done before) will force us to look at our teaching afresh and, by providing us with new challenges, has the power to revitalise our professional lives.

Finally, some teachers become involved in the running and organising of teachers' associations. Most associations allow any member to stand for election and there is no doubt that those who become committee members, treasurers and presidents of, say, IATEFL or TESOL get a huge amount of personal satisfaction from being involved in running organisations like this.

Being well

Teachers need to care for their bodies to counteract stress and fatigue. Katie Head and Pauline Taylor (1997: Chapter 6) suggest techniques for breathing and progressive relaxation. They advocate the use of disciplines such as Tai-chi, yoga and the Alexander technique to achieve greater physical ease and counteract possible burnout.

One of a teacher's chief physical attributes is the voice. Roz Comins observes that at least one in ten long-serving teachers need clinical help at some time in their career to counteract vocal damage (1999: 8). Yet voice is part of the whole person, both physically and emotionally. When we misuse it, it will let us down. But when we care for it, it will help to keep us healthy and build our confidence. We can do this by breathing correctly and resting our voice and ourselves when necessary. We can drink water or herbal tea rather than ordinary tea, coffee or cola if and when we suffer from laryngitis; we can adjust our pitch and volume and avoid shouting and whispering.

Many teachers work long hours in stressful and challenging situations. At the primary level they seem to be vulnerable to many of the minor illnesses that their students bring with them to school. Keeping healthy by taking exercise and getting between six and a half and eight hours’ sleep a night are ways of counteracting this.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.